The beauty of hardware

April 27, 2020

My life is tied to software. I first got interested in it in the year 2001, when I saw my father reading a C++ book. Since then, I learned and built and failed and learned again up to this day. Over those years, I’ve learned about different programming languages, peeked into the inner workings of operating systems, databases, and compilers. Back in the old days, I have tried to build simple bootloaders and operating systems in assembly using my old PC-iMac clone.

Yet, somehow, I have always avoided getting into hardware. How does a CPU work? How RAM stores a single bit of memory? It was all black magic to me. Computers just worked. Maybe, your case is the same as mine. In this post, I will provide a short intro to digital electronics and give you some references on how to advance your studies further.

During my first attempt to learn electronics, I knew some basics about the CPU architecture and could assemble a desktop computer to write my software, and that was it. I’ve tried to get into hardware during university years. I had no access to simple to use development boards like Arduino at the time, so my DIY microcontroller LED blinker was brick-walled by the necessity to learn how to solder the dev board myself. I used hardware as an abstract entity for more than a decade, until I’ve encountered Ben Eaters YouTube channel and his series of videos about building a 8-bit Turing-complete computer from scratch. The first few videos covered the basics of creating a clock circuit using a 555-timer integrated circuit. It turned out that hardware makes sense too. In many ways, it’s a lot like programming. You have a lot of different components with functionality literally encapsulated into the plastic case. You connect those components together to create more complex behaviors. And that’s about it. Of course, that is about digital electronics. Analog circuits are more complex to design and understand. Also, designing and manufacturing an integrated circuit itself is hard, but you wont . After Ben Eater’s video series I read the CODE by Charles Petzold. The book does a great job of guiding you in how computers work from lightbulbs and telegraph relays to operating systems. It also tells some fascinating stories from the history of computing along the way. I recommend both resources if you want a good introduction to digital electronics.

The interesting fact about learning electronics is that you will build unexpectedly many connections between your hardware and software skills. Bitmasks will start to make sense, and you’ll get fancy references like tx and rx naming conventions from Rust std::sync::mpsc That leads us to tx and rx pins in asynchronous serial communication interfaces . You’ll see how the history of hardware influences our professional lives. For example, many roles in software development take their roots in hardware engineering. Look more closely at the software architect, who draws diagrams and you’ll see a PCB designer. Or look at the many companies that call themselves a systems integrator and you’ll see their projects have analogies to connecting various ICs Integrated Circuits in a PCB.

The concepts of abstraction and encapsulation are used in hardware much like they are used in software engineering. To see this, we’ll go through the basics of digital electronics.

What is digital electronics

The electrical signals are inherently analog. Electrons, that move through conductors create an electrical current that we measure using different quantities such as Amperage, Voltage, and Resistance. So, how it comes that we can leverage the movement of electrons to create Turing-complete computing devices? To understand this, we first need to dive into mathematical logic.

Mathematical logic formalizes logical reasoning into mathematical objects, that we can use to prove theorems. The subset of this field called Boolean algebra is of particular interest to us. Boolean algebra defines a set of operations on Boolean variables. Each Boolean variable can hold two possible values: True, or False. Those are also frequently represented by 0 and 1. The basic operations of Boolean algebra are or , or and or If you were able to read that sentence, you already have a good idea of how these basic operations work. .

- when and are the same

- when either or are 1

- reverses the value of x

Those functions can also be represented graphically:

Ok, so we got a concept of Boolean variables and a bunch of functions that change their values. Things start to get interesting when we find isomorphisms Isomorphism is a mapping between two structures of the same type that can be reversed by an inverse mapping. See Wikipedia between different areas of mathematics and Boolean algebra. For example, you can map any natural number to a binary number, that is represented only using zeros and ones. For example, 0 is 000, 1 is 001, 2 is 010, 3 is 011, 4 is 100, and so on. This operation is called a change of base. In this case, we change a base of decimal number (base 10) to binary (base 2). You can also find ways to represent signed numbers and rational numbers in binary form. This means that we can manipulate numbers using binary functions by:

- Transforming the number to its binary form

- Applying a set of Boolean operations to the number

- Transforming the resulting binary value back to decimal base

The next question is if there is a way to represent regular mathematical functions such as addition using Boolean algebra operation. And the answer is, of course, 1. Pun intended For example, you can add two binary digits by using 5 operations Read about the full-adder if you are interested in more details. .

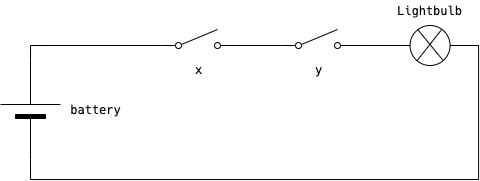

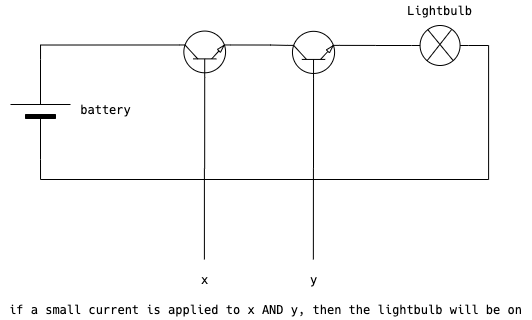

So, Boolean algebra and binary numbers can be used to make complex computations and apply formal logical reasoning to numbers. If we would be able to implement Boolean algebra in the physical world, then we would be able to manipulate numbers using artificial devices instead of our brains. It turns out, that we can implement those with nothing more than several switches and a battery. Look at the following diagram:

Here, you can see a battery, two switches, and a lightbulb. The current flows from one terminal of the battery to the other if there is a connection between them. It is pretty simple to deduce that the light will be on only when the two switches are closed. If we will label the absence of electrical current as 0 and the presence as 1, then the lightbulb will behave exactly as , where is the first switch and is the second.

Similarly, we can build an OR gate using the same two switches, but connected a bit differently:

You can check that the lightbulb will be on when either OR will be on. And here is an example of the NOT gate:

As you can see, any logical function can be represented using switches. This means, that we can build anything that manipulates numbers, in the physical world! Of course, building a sophisticated circuit such as added using regular switches is complicated. Also, our final device will be huge and hard to maintain. Consider how tiresome it could be to search for a broken switch. Another issue is that someone should manually put those switches on and off. Thankfully, a man named Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring designed a switch that can be controlled using electricity: a relay.

Relays are switches that are turned on and off using electromagnets. Originally, they were invented for entirely different reasons. Relays were used to repeat an electrical signal in telegraph lines so that it could be transferred to large distances without using thicker wires Electrical current needs thicker wires if you want it to travel over long distances. The longer the wire is, the higher its resistance will be. Thus, if you are sending a current over large distances, you may experience a voltage drop at the other end of the wire. Making the wire thicker will the lower is the resistance, which in turn will compensate the voltage drop. .

Relays are were a breakthrough, but they had some severe issures: they are costly, large, and they break often. Computers that used relays were big and noisy. If you want to hear some satisfactory clicking, play a video below:

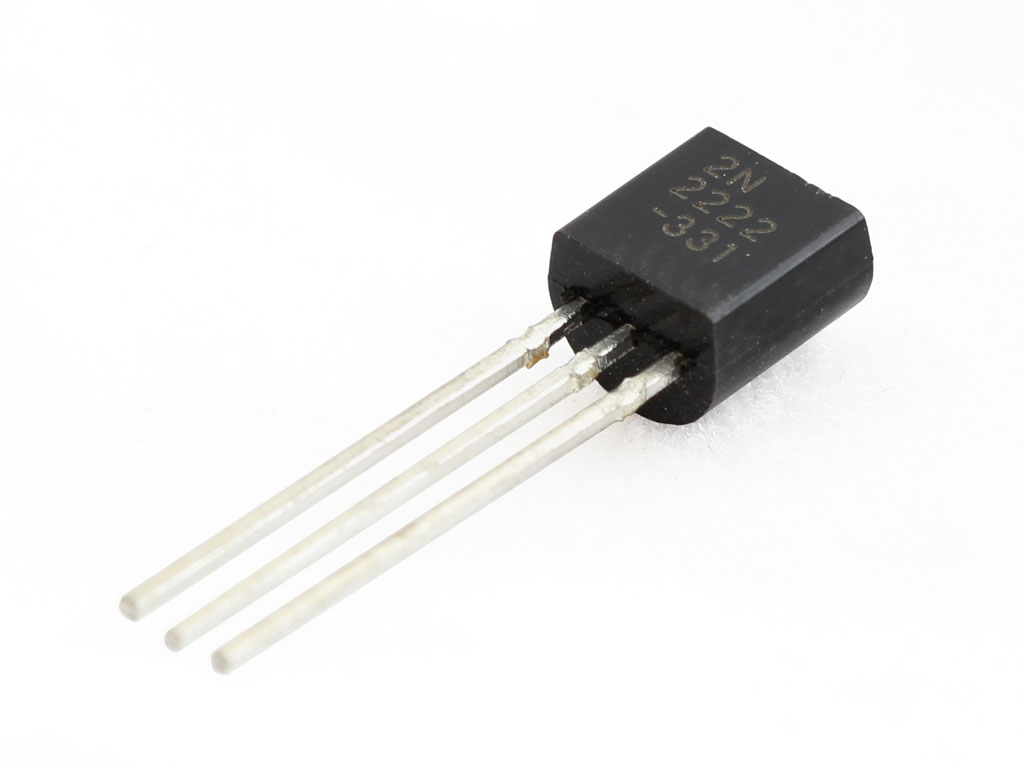

Since the device that you use to read this post is not sounding like an electrified drummer, we can deduce that something had replaced relays during technological evolution. The thing is called a transistor. Transistor has an arguably fancier name, but it’s functioning almost the same as a relay. The major change is that there is no physical switch inside anymore.

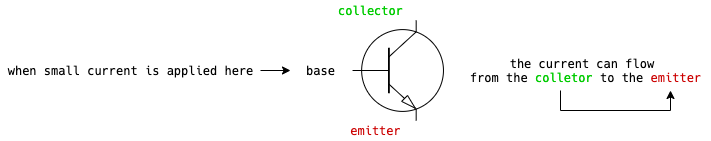

Each transistor has three pings, which are called the base, the collector, and the emitter. Imagine that the collector and emitter are the ends of our old trusty switch. Then the base will control whether the switch is open or closed. If a small electrical current is applied to the base, then the switch closes and the current can flow between the emitter and the collector. Let’s look at how the transistor operates using a diagram:

Now, let’s look at how we can implement using transistors:

All action happens at the atomical level. This means that transistors can be small, very small. For example, an Intel Core i7 Broadwell processor contains around 1,750,000,000 transistors on a single chip.

Wrapping up

Now, you’ve seen that digital electronics is a lot like programming: you have a set of basic abstractions that you can use to build more complex things. Like software modules, hardware abstractions are packaged into Integrated Circuits, which you can use to build devices with more complex behaviour. If you want to dig in, continue with the following resources: